Michael Neill shared the poem If by Rudyard Kipling on a call I was on with him a few weeks back and it struck me as an excellent thing to share with you.

The way of traveling through life described in the poem is entirely possible. It is the promise of the sort of understanding I attempt to share with you here each week.

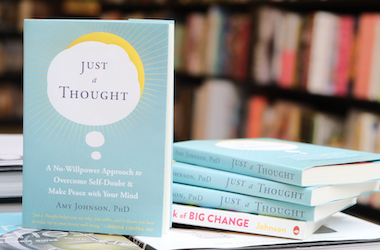

It also reminded me of the thus far fictional portion of my book I wrote about my son, called How to Live with Your Mind at Ease, Reveling in the Experience of Being Alive. I’ll share that beneath the poem, in case you haven’t read Being Human (yet, obviously).

If by Rudyard Kipling

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise:

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

How to Live with Your Mind at Ease, Reveling in the Experience of Being Alive (from Being Human)

There once was a boy named Miller.

He was born a perfect baby–as all babies are—on a perfect January morning just before sunrise. Of course his mother thought he was remarkable in many extraordinary ways but in reality, he was no more or less perfect than any other baby who had ever been born.

Miller’s mind was at ease and he reveled in the experience of being alive.

He acted without reflection. Miller didn’t take the actions of people around him personally because he didn’t conceive of a “self” that was separate from “them”. With things out in the world not about “him” in any way, life was infinitely easy.

Miller experienced life as it unfolded as purely and unfiltered as a perfect baby can.

He appeared to feel content quite often, but he experienced a lot of other emotions too. His parents described him as a mostly happy baby, but he certainly wasn’t always happy. He cried a fair bit (especially as his parents were hoping to sleep at night) and became angry (at the suggestion of drinking from a plastic bottle rather than directly from his mother) at times. He also experienced what looked like fear (of the vacuum cleaner), frustration (at painful incoming teeth), and disgust (two words: scrambled eggs).

To the adults around him, Miller appeared to cycle through a wide range of emotions quite swiftly and naturally, like a scattered thunderstorm passing overhead.

Miller’s mind was at ease and he reveled in the experience of being alive.

As he grew older, Miller began to see boundaries. Faint at first, he nonetheless formed the concept of a “self” as distinct and separate from the rest of the world, first evidenced when his older sister was handed a snack he ran over yelling “me, me, me, me!” The adults in his life found this rather adorable despite the fact that he was clearly becoming more like “them” (a thought that made his mother proud, but also a little sad).

Miller’s emotions began to “stick” as he grew older. Rather than assessing his mood moment to moment, his parents began to say things like “Miller is being silly today” or “Miller is having a tough afternoon”. Of course, those statements probably reflect his parents’ biases as much as his own evolution, but his emotions definitely appeared to become less transient as he grew more verbal and intelligent.

Nonetheless, Miller’s mind was at ease and he reveled in the experience of being alive.

As he grew into adolescence, Miller thought about “himself” more and more, but he always remembered the truth; those boundaries he saw between himself and the rest of life were illusory. Because he knew that, he tended to behave more kindly toward other children and the world around him than some of his young friends. Don’t get me wrong: Miller was like other little boys, for the most part. But it rarely occurred to him do things like throw trash on the ground or call kids at school names. Those behaviors simply didn’t cross his mind much and if they did, he dismissed them.

He didn’t try very hard to figure things out because—in his experience—most problems in life figured themselves out. Making that his job (the way the adults around him seemed to), looked a little senseless to Miller.

Miller knew that the thoughts that ran through his mind were fleeting and meaningless. He didn’t take them very seriously most of the time; he simply noticed them with curiosity or disinterest.

This wasn’t always true—like all humans, he got caught up in his thinking from time to time. His thought-storms tended to be calmer, shorter, and less destructive than his friends’, however, because he understood the fleeting and biased nature of thought. Why get caught up in something that wasn’t real and would change in a flash?

When Miller was feeling particularly unpleasant he remembered what his mother had always told him: You’re always and only feeling your thinking and thoughts and feelings are nothing to be afraid of. He understood that thoughts and feelings come and go, and that there was nothing in his experience to fear. That seemed to help him bounce back quite quickly and he rarely felt stuck in a bad feeling for very long.

Miller’s mind was at ease and he reveled in the experience of being alive.

As a teenager, Miller had his share of ups and downs. Things didn’t always go his way. The girl he loved broke up with him one day and that threw him for a loop. He felt deep sadness, then anger, and then loneliness. He questioned his own worth, like humans are wont to do.

But Miller knew something not all teenage boys know: he knew he would bounce back to the underlying peace and connection that was there in all of life. Because peace and connection were who he was—his true nature—he knew he’d effortlessly return there and he didn’t have to actively do anything. He didn’t have to “get over the girl” or “move on” at all; those things would happen naturally on his behalf. Knowing that he wouldn’t get stuck in his dark feelings forever made the darkness a wee bit lighter. He still wanted his girlfriend back but, well, such is life. A deeper part of him knew he’d always be okay no matter what.

Miller’s mind was at ease and he reveled in the experience of being alive.

As Miller grew into a man he delighted in life, just like he had as a baby. He embraced change and welcomed challenge which gave him a somewhat revered status among other adults. They looked at him and thought, “What is it with that guy? Is not afraid of anything? Does he not care what people think, or that he might fail, or that he could lose everything?”

The truth was that sure, daunting scenarios of letting down his family or ending up in a van by the river occasionally passed through his mind. But Miller knew that those thoughts passed through all human minds from time to time—he didn’t believe they were his alone. He saw through their scary tone and the feelings they brought with them. They were more like shadows on the wall that only look like a monster than they were any kind of real monster. As such, he dismissed them relatively easily.

Miller followed his heart with reckless abandon because he knew he ultimately had nothing to lose. Peace and contentment were his birthright—they were who he was, not things he had to earn. He couldn’t earn them any more than he could lose them so he simply didn’t take circumstances so seriously. Peace and contentment weren’t at stake so life looked rather safe to Miller.

He scratched his head as he watched his friends worry themselves sick over landing the “right” job or as he watched them fail to go after their dreams because “what if it doesn’t work out?” or “what will people think?” Because Miller knew without question that he could have a wonderful life regardless of the details, he simply wasn’t held back in the same way. He did what he wanted to do and bounced back from disappointment easily.

Miller’s mind was at ease and he reveled in the experience of being alive.

Miller was kind to himself. He felt compassion much more than judgment toward himself and others. After all, he reasoned, we’re all just humans doing what we believe is best. No one was truly to blame for what they do—what good was blame? Blame and judgment require some objective right and wrong and Miller didn’t quite see the world that way. He believed that people did what made sense to them given their current thinking—and he certainly couldn’t fault someone for falling into the same insecure thinking that all humans fall into now and then.

So while Miller lived through the same up and down circumstances as the people around him, his experience of those circumstances was quite different. And while he felt the same dark emotions from time to time, his comfort with those emotions ensured that he bounced back from them very quickly.

Miller’s mind was at ease and he reveled in the experience of being alive.

Miller spent his life doing the things he loved most. He played a lot. He loved a lot, worked a lot (on things that felt like love), and enjoyed deep connection with the people around him. He often felt as if he were being guided through life. Miller loved using logic and his incredible intellect to solve puzzles and satisfy his intellectual curiosity, but he understood the limits of his thinking mind. He was often quietly tapped into what he called “Big Mind” and it felt miraculous–like home.

Miller’s mind was at ease and he reveled in the experience of being alive.